I was born on the mountain and the mountain is in me. It is in August, last liminal flicker of summer, that I feel the coolness of the mountains call me back. If we are made of stardust and memory held fast by the people and places we have loved, then I carry within me a bit of the mountains that I, and my mother, and her father before her were born to.

It's not homesickness, I never had a "home" to be sick for. I went to more than 17 different schools before I graduated and I missed almost as many days as I showed up. We never stayed put very long. We lived partially out of the system's pocket, my mother and her husband worked or hustled when they had to, skipped town when they wore out their welcome, partied for days in between. We crossed the states from east to west coast and back again, sometimes in campers or vans. Other times we camped or stayed in hotels, swam in over chlorinated pools all day while he earned enough to pay for that night. Some seasons we retreated from the city laid low on the mountain. I was born a restless traveler with no roots to hold me back or to tether me to that which was solid. It was a transient and strange childhood, but all childhoods are a little strange. Mine is just harder to explain. I feel like a fraud when people ask me where I am from. I'm not from anywhere, there is no place I miss or wish for, no real place where my bones say "ahhh, right here's the spot that I belong."

"I think that one is always attached to the places where you spend your childhood, in the summers." Frank Cabot, from The Gardener

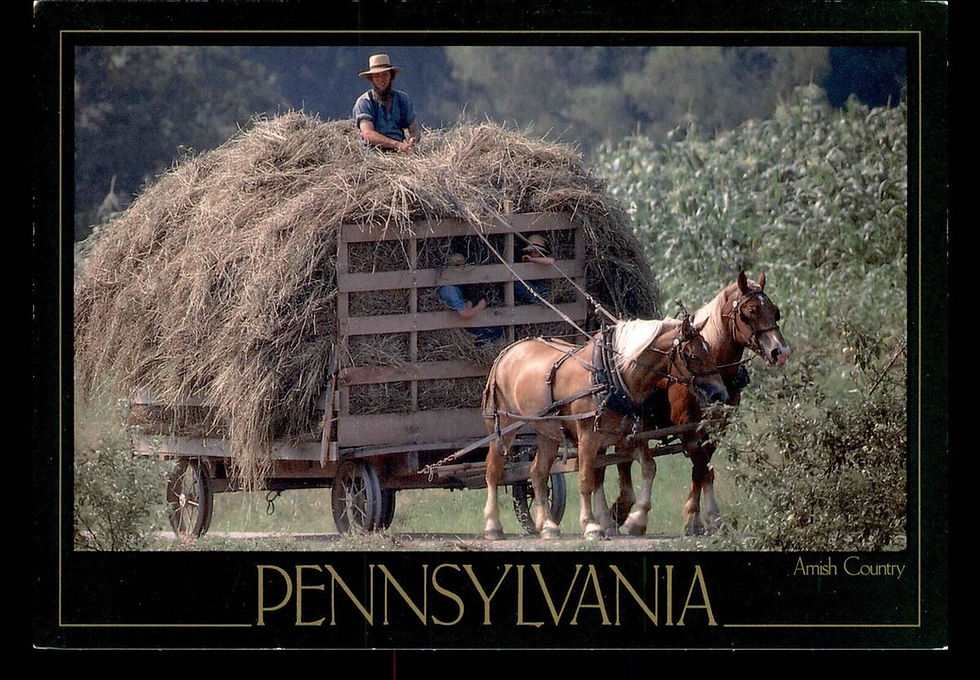

August was for making hay, to stand in golden shimmer of the afternoon sun listening for the crush of gravel under hoof and wheel. Twice a day during hay making season, a pair of enormous Belgian draft horses pulled an open hay wagon up the winding narrow road of the mountain; a crew of Amish, men and boys passed in silence, once at daybreak and back again after the long work of the day was finished. I was there to witness the horses, the pack of Amish were the by-catch.

The horses were a sight to see, straining muscles wrapped in chestnut velvet, large intelligent eyes shielded by blinders. They were calm and steady, ignoring a pair of young hounds that darted impossibly unscathed between the massive sturdy legs. Descendants of the old world breed brought from across the ocean a century before, the strong draft horses could tolerate the long and brutal winters, they could pull the heavy plows that churned the rich earth of the valley into obedient rows. When the wagon disappeared around the bend, I would scramble down from my vantage point and stepped my own bare foot into the dinner plate size indentations from their hooves.

Only a few families on the mountain were "Englisher" which is how the Amish have always differentiated outsiders. This family was of the strictest Ordnung, socializing only with other Amish, so when they glimpsed me in the bend, standing above a bank of established tiger lilies, they stopped their High German chatter and averted their eyes. I felt like a ghost. Two young boys knelt on the floorboards and jumped from the wagon, swift and shoeless, to clear any fallen branches from the path and to open the long metal gate to the cow pasture adjacent to the southern the property we lived on.

In their bearded silence, I heard the panting of the dogs, the scattering of pebbles kicked, the rhythmic grunt of wooden wagon against metal axle, the low sighs of the horses. Dragonflies paused, the rust speckled lilies bowed and curtsied. A glimpse of that rare plane, time, suspended in the spun honey of late summer sun. Here was my August, in eternal amber.

I remember the plants of this place. Not just the late summer tiger lilies, by the road, but also the purple bearded irises that stood as prim as Sunday school teachers around the ring of a Leviathan walnut tree. Soon that walnut tree would drop green tennis balls that sweatered bitter black walnuts. A smooth barked lilac whose pretty fingers tapped against the kitchen window. She came to life in May and I would walk back and forth under the low branches hoping to absorb the most beautiful fragrance on earth through some type of osmosis. It was hopeless to cut any lilac blooms to bring inside, the tender blooms wilted off the woody stems almost immediately. They were best enjoyed on tap.

The closest "Englisher" neighbor was half a mile away, but it was worth the short walk when her Lily of the Valleys trembled to life. A pear tree knobby as an old man's fist. A money plant near the wash line, in August the pods were the green of a summer frog, as autumn closed in on the mountain, the pods turned to silvery coins. The Amish called it a Judas plant, for the silver coins used to betray Jesus. A pine sentinel guarded the western face of the house. It stood very close to the foundation of the dilapidated 3 story house and I figured out how to use the porch to jump start my climb. After the time I waved through a bedroom window to my mother while she vacuumed (and gave her a terrible scare!) she made me promise not to climb past the pitch of the porch roof. I spent hours in that tree, I jammed books into the waist band of my corduroys and read with my feet dangling. I talked to the tree quite a bit, and sang all the songs I could remember, which were usually only Christmas songs or commercial jingles.

August was for bare feet, a life without hateful southern fire ants or boiling city pavement. The grass was cool and inviting and the moss was even better. Moss is the first plant I remember looking at very closely. Lush banks of it under the branched shade of the wood line I loved. I saw the trees as forms frozen in mid conversation, waiting for me to pass before they continued the story. I taught myself to walk quietly in hopes of walking into their banter. I was sure, like the Amish, the trees resumed their chat as soon as I was out of earshot.

The Germans have such clever words for feelings with moving parts. My daughter taught me "Kummerspek" which means "grief bacon", the weight gained from emotional eating during times of stress. Or the infamous "shadenfruede" which is joy in the misfortune of others (ouch). What is the word for the quilt of the forest closing behind you, the cool whisper of many trees matching their breath to yours? The quality of light from our closest star filtered through many branches?

It's the stones I miss even more than the trees, granite monoliths left exposed during the retreat of glaciers during the last ice age. Boulders the size of elephants to climb and clamber over. The stones held the warmth of the sun and the cool of the starless night. They have personalities of their own, these stones, the bones of the mountain. I find myself looking for stones on my walks, hoping they will find me. I'm lucky if I find a stone larger than a duck egg in Mississippi, the red clay, loose flesh with no bones, goes on forever, like the August heat in my new place.

My mother's father, Pap Forney, could disappear into the mountain without a word to anyone, emerging from the dense woods with a deer slung over his on his shoulder just as silently the next day. Bantam rooster though he was, he was tough as they come. He made homemade fireworks and fished with explosives (illegal, illegal). He bartered for a used milk truck, painted it camouflage, mounted spotting lights on the frame, overhunted and sold the meat (illegal, illegal, illegal) My grandfather built lean to stills deep in the mountains, where the police where far too lazy to go (illegal). Pap smoked Pall Malls with the filters ripped off; he said you should always carry a comb, a handkerchief, and a knife. He had a fantastic head of hair and I never saw him without his shirt tucked in.

On Sundays he cleaned and stocked the Nitty Gritty. I polished the long wooden bars and brass fixtures, wiped fingerprints from the glass liquor bottles, and combed the green felt of the billiards tables with a bristled brush made just for the purpose. It was not a fancy bar, but it was old, and he lived in an efficiency above the bar in exchange for his work as caretaker. He was a hopeless drunk; he knew every trade but couldn't keep a job, nor did he care to. If I did a good job on the billiards tables and passed inspection he poured me a ginger ale from the bar while I perched on the worn leather stool like a miniature Queen of Sheba. When the last ashtray had been wiped out and the true believers started to line up outside for noon when the Blue Laws were satisfied, he drove me back to my mother. I sat in the front of his ancient Ford without a seatbelt while he belted out Frank Sinatra's "Ain't She Sweet" and pinched my cheek during the chorus. That was always his song for me, his first grandchild.

He died in a VA hospital. Withered from whiskey and cancer. All of his daughters were around him; in the end they snuck in booze in 35 mm film containers for their father, poured it into his coffee, held his head so he could drink it. Made jokes that the food was better when he was imprisoned in a POW camp. No one could remember a day he stayed sober. He gave us his blue eyes and his curling hair. It was in August and we buried what little there was left of him on the mountain.

I traveled to Scotland when I studied abroad at Oxford. Edinburg and Glasgow were easy to explore alone and on foot, but Inverness and farther North were more accessible through arranged tours with locals. Bouncing around in a windowed van were myself, a young women from New Zealand, a middle aged English couple, and four young male students from Mexico City. They spoke very little English and froze in their light windbreakers, but in general were merry company. Every time the van stopped at some historical marker (spoiler alert: all battlefields), they huddled together laughing and dribbling a soccer (foot) ball amongst themselves. Unbeknownst to we, the intrepid travelers, our tour guide was training a passel of young understudies, so six more Scots traveled with us. It was a bit daunting, as foreign strangers in an unmarked van to be jetting off to the great wild practically outnumbered by eager hosts, but it proved a great joy to have so many locals ready to share their culture and country.

On the 3rd day, our hosts presented the Highlands, with not a small flourish and a with tangible pride. I was not underwhelmed, but I was confused. Perhaps my captors had drugged me with their weak tea and floated our van across the pond, because surely I was in the mountains of...Pennsylvania? (Scotland and Pennsylvania pictured below, which is which?)

Because the rest of the world teaches actual geography, one of the guides explained it to me at the pub that evening. Folding a napkin, he drew a sea of triangles, the mountains. The continents married together as Pangea and the forest of points were the Central Pangeans. He pulled the paper napkin apart, showing how the great plates shifted, heaved, broke from one another; the Scottish Highlands, the Atlas Mountains, and the Appalachians are sister mountains, born at the same time 340 million years ago. I wonder if they miss one another. If they call to each other across the great seas. If the mountains feel the loss of their siblings, if that's why they call their children home.

The Gardener (Award Winning Documentary on les Jardins de Quatre-Vents)